IN MEMORIAM

Best known for her portrayal as Carla Grey on “One Life to Live,” a role that marked the first time a black person had starred in a daytime soap opera, actress Ellen Holly has died. She passed away peacefully in her sleep on Wednesday at Calvary Hospital in the Bronx, New York. She was 92 years old at the time of her death.

“She was a pioneer in daytime television. Starring on ‘One Life to Live’ for 20 years. Playing Lawrence Fishburns [sic] mother on the show. She appeared in several movies, and performed on stage with the greatest black actors of her generation. Sidney Poitier, Harry Beafonte, Cicely Tyson, Robert Hooks, [and] James Earl Jones, to name a few,” said Holly’s cousin, Grant Shipp, in a post on Facebook. “You had ‘One Life to Live’ and it was amazing Life. You were simply one of the best. Now you know the secret. God rest your soul.”

Born January 16, 1931 in Manhattan, NY to parents William Garnet Holly, a chemical engineer, and Grayce Holly, a housewife and writer, Ellen Holly was part of a prominent Black family that included her paternal great-grandmother, Susan Smith McKinney Steward, the first African American woman to earn a medical doctorate (MD) in New York State and the third in the United States.

Holly’s great aunt was Minsarah Smith Thompson Garnet, a suffragette and the first Black female principal of a New York City school; Minsarah’s husband, the Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, an abolitionist who was appointed Minister (ambassador) to Liberia by President James A. Garfield; her great-grandfather the Rev. James Theodore Holly, the first African American to be ordained a bishop in the Protestant Episcopal Church and a prominent missionary to Haiti; and her great-great grandfather Sylvanus Smith, one of the leaders of the movement urging Black people to purchase land in Kings County, New York, in an area later known as the Weeksville settlement and a landowner there.

Additionally, Holly’s maternal aunt Anna Arnold Hedgeman was the first Black woman to be in the cabinet of a New York City mayor (Robert F. Wagner Jr.), one of the lead organizers of the March on Washington and a founding member of the National Organization of Women.

Growing up in Richmond Hill, Queens, NY, Holly became a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. during her college years at Hunter College, where she graduated. Later, she began acting on New York City and Boston stages, earning instant critical acclaim. She made her Broadway debut in “Too Late the Phalarope” in 1956, and she went on to star in the Broadway productions “Face of a Hero,” “Tiger Tiger Burning Bright” and “A Hand is on the Gate.”

From 1958-1973, she led productions of numerous Joseph Papp New York Shakespeare Festival productions. Throughout her years in the theater, she worked opposite such luminaries as Roscoe Lee Browne, James Earl Jones, Jack Lemmon, Barry Sullivan and Cicely Tyson. Holly also studied with dance pioneer Katherine Dunham and was passionate about the role of dance in revealing the richness of African-American culture.

Prior to her groundbreaking role on “One Life to Live,” Holly’s television credits included “The Big Story” (1957), “The Defenders” (1963), “Sam Benedict” (1963), “Dr. Kildare” (1964) and “The Doctors and the Nurses” (1963 and 1964).

Holly was personally chosen for the role of Carla Grey by “One Life to Live” and “All My Children” creator Agnes Nixon, who had read a New York Times opinion piece that Holly wrote called “How Black Do You Have To Be?” which talked about the difficulty of finding roles as a light-skinned Black woman.

As the first time a Black person starred in a soap opera, it was a watershed moment, coming as it did during the turbulent and racially divisive 1960s.

Her character’s attempt to come to terms with her racial identity and her love triangle with two doctors — one White, the other Black — helped launch viewership of the nascent soap opera into the stratosphere.

With Holly appearing in the pages and on the covers of publications like Newsweek, TV Guide, Ebony, Soap Opera Digest and The New York Times, daytime television soon exploded with Black storylines being featured on “All My Children” and “General Hospital,” which helped ABC dominate daytime for two decades.

In later years, Holly spoke out about being underpaid and other mistreatment she claimed she and some of her fellow Black cast mates received from show executives despite their contributions to the show’s success.

After exiting “One Life to Live,” Holly went on to appear in a recurring capacity as a judge on “Guiding Light” from 1988-1993. She also appeared in episodes of “In The Heat of the Night” from 1989-1990, along with the television movie “10,000 Black Men Named George,” working opposite Andre Braugher and Mario Van Peebles.

On the big screen, Holly appeared in “Take a Giant Step,” “Cops and Robbers” and Spike Lee’s “School Daze.”

In the 1990s, Holly took the civil service examination and became a librarian, serving as such for many years at White Plains Public Library. In her autobiography, she referred to her years there as some of the happiest of her life.

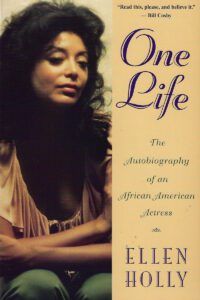

An accomplished writer, Holly continued to write numerous pieces for the New York Times. But in 1996, she finally got to tell her life’s story with the publishing of her autobiography, “One Life: The Autobiography of an African American Actress.”

With a reflective life dedicated to the arts and civil rights causes, in her final years, Holly began preparations for a documentary about her life and the storied activism of her family.

A beloved member of the White Plains community, Holly was predeceased by her younger sister, Jean H. Gant, and her niece, Holly Gant Jones. She is survived by her grand-nieces Alexa and Ashley Jones (White Plains), daughters of her beloved niece, Holly Gant Jones, who predeceased her, and their father, Xavier Jones; first cousins Wanda Parsons Harris (Dayton, Ohio), Julie Adams Strandberg (Providence, Rhode Island), Carolyn Adams-Kahn (New York), Clinton Arnold (Los Angeles) and a host of other loving family members.

Watch clips from Holly’s four-and-a-half-hour interview with the Television Academy in which she talks about her early life and her paternal family tree going back to the 1700s. She also discusses becoming interested in acting and her big Broadway breakthrough in “Too Late the Phalarope,” among a plethora of other topics.